Statement of Research Interests and Career Goals

Microbes constitute the bulk of the biodiversity and biomass on Earth and have critical impacts on the function of ecosystems including remineralization, and carbon production. Since Pomeroy (1974) suggested the importance of micro-heterotrophs for carbon fluxes in marine systems, it has become increasingly clear that microbial eukaryotes or protists play a key role in our ecosystem, in particular within the planktonic food web. Microbial eukaryotes, the focus of my work, are the intermediate between small animals and both bacteria and their autotrophic congeners (Azam et al 1983; Sherr & Sherr 1986). For example, microbial eukaryotes are responsible for 50-85% of the oxygen production (mainly phytoplankton) and are at the base of trophic webs. It is therefore critical to better understand relationships between microbial eukaryotes and their environments. This includes, but is not limited to, examining the trophic links between microorganisms and both their food resources and predators and the impact of abiotic factors (e.g., temperature, pH).

Keywords: Ecology, Biodiversity, Planktonic food web, microbial eukaryotes, SAR clade

As graduate student in France, postdoctoral fellow at Smith College and at Temple University, I examine the role of protists, mainly in marine system, using microscopy, molecular tools (e.g., metabarcoding, single-cell and community ‘omics), and bioinformatics; from in situ and experimental observations and from species to community. My research program will have the aim of reconciling genetic estimates, ecology and evolution, and is composed of three strongly interconnected parts:

An explorative approach :

assessing the diversity of microbial eukaryotes in understudied environments such as deep-ocean, freshwater, soil, and built/ human made environments using molecular and morphological tools. In this part, we will look at closely related species, and their ecology – What makes them different from each other?An experimental approach :

estimating the functions of the microbial eukaryotes through cultures and/or microcosm experiments to assess physiological responses, coupled with transcriptomics to assess genes involved – What is the amount of redundancy in the system? and what makes the various versions of the same gene different from each other?And a modeling approach :

determining the ecology of microbes by combining knowledge from explorative and experimental approaches and from literature. Can we predict the short-term community change and the long-term evolution? – e.g., What will be the next dominant species, or the potential future variants based on known environmental factors?Together, these approaches and my qualifications will allow a better understanding of the protists, of the food webs, and their evolution. They will also make it possible to better understand (1) what a microbial eukaryotic species is using functional traits, morphology and genomic; (2) what the effective population size of a microbial eukaryotic species is; and (3) what the scale of evolution is -- e.g., does a species cultivated in the lab evolve within a similar time frame compared to a species in the wild? Does a species lose functions when cultivated under optimal conditions?

Microbial eukaryote diversity:

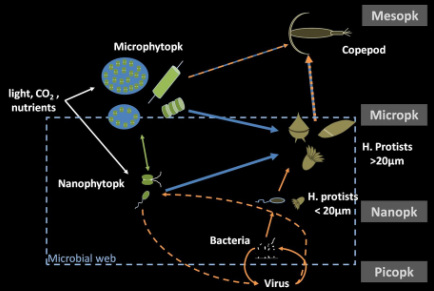

Model of the fluxes estimated and observed during the in situ survey and microcosm experiment in the Eastern English Channel (Grattepanche 2011, PhD defense)

During my graduate training, I examined the community structures and succession of phytoplankton, microzooplankton and mesozooplankton (copepods). This work highlighted: (i) the seasonal and annual variability of heterotrophic protists and its strong relation to phytoplankton succession, bloom magnitude and duration (bottom-up control), and to the presence of predators such as copepods (top-down control; Grattepanche et al 2011a); and (ii) the importance of dinoflagellates as major consumers of phytoplankton, particularly with a size > 100µm and ciliates as very efficient grazers of nanoplankton (<10 µm; Grattepanche et al 2011b). The work indicates the importance of species-specific relationships among microbial eukaryotes and provides greater details on the ‘black boxes’ within the planktonic food web.

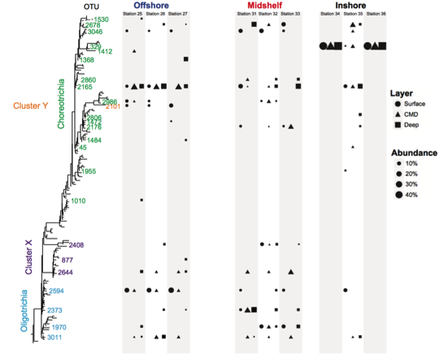

While patterns of abundant community members can be observed by using “classic” tools such as microscopy, clone libraries, DGGE (Grattepanche et al 2014a, 2015, Tucker et al 2017), the use of high throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies allow observations of patterns at finer taxonomic scales. One of the more dramatic insights from HTS has been the discovery of numerous rare lineages of both bacteria and archaea in natural environments (i.e., the rare biosphere; Sogin et al 2006) as well as tremendous diversity of eukaryotes in our analyses (e.g., Santoferrara et al 2014, 2016; Grattepanche et al 2014b, 2016a and b; Sisson et al, 2018). Assessing the diversity of eukaryotic microbes requires accounting for both the technical limits (e.g., bias, accuracy, sample size) and the heterogeneity in units of biodiversity (e.g., species) that vary based on analyses of molecules, morphology and behavior (Grattepanche et al 2014b).

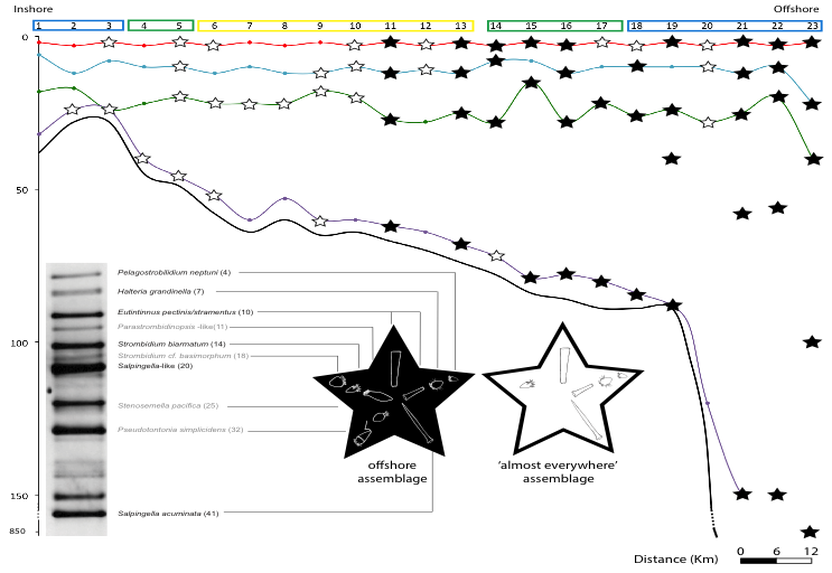

Ciliate assemblages observed off the coast of the New England using DGGE (Grattepanche et al 2015)

Ciliate assemblages observed off the coast of the New England using DGGE (Grattepanche et al 2015)

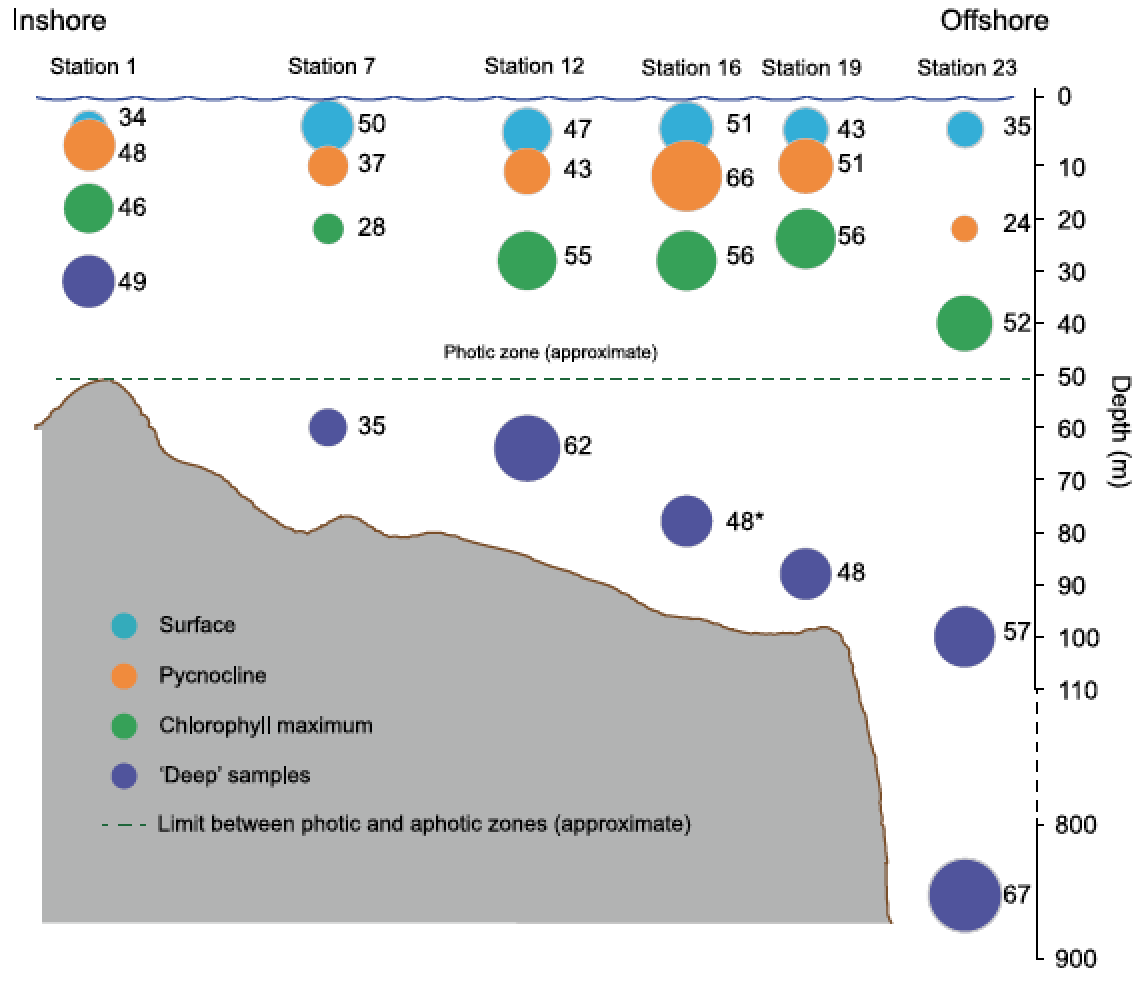

Distribution of OTU richness for each sample shows a complex pattern but overall a relatively high number of OTUs within the deep samples compared to the sample taken above (Grattepanche et al 2016).

Distribution of OTU richness for each sample shows a complex pattern but overall a relatively high number of OTUs within the deep samples compared to the sample taken above (Grattepanche et al 2016).

Analyses of HTS data on ciliates from coastal waters in New England reveals an increase of diversity with the depth, particularly below the photic zone (Grattepanche et al 2015, 2016), which contradicts previous estimates based on microscopy and clone libraries (e.g., Christaki et al 2011, Wickham et al 2011). The environmental parameters measured did not well explain the pattern of ciliate communities observed (e.g., Grattepanche et al 2015, 2016). A focus on smaller scales shows that individual OTUs have distinct biogeographies and that the community pattern is patchier than expected (Grattepanche et al 2016b), adding more confusion to our understanding of the microbial eukaryote ecology: ‘some things are everywhere and some things are not. Sometimes the environment selects and sometimes it doesn’t’ (van der Gast, 2013). Using vernal pools as study system, I observed that the microbial eukaryotes found in soil can represent a seed bank which allows for community turnover: taxa encysted in the sediment in poor environmental conditions excysts when favorable conditions are met (Sisson et al 2018). This can be one mechanism allowing the boom-bust cycle observed at small scale.

Future Direction:

While microbial eukaryotes, especially ciliates, in the surface ocean has been the subject of a lot of attention (e.g., de Vargas et al 2015, Massana et al 2015 and my own manuscripts), microbial eukaryotes are still little studied in terrestrial and freshwater environments, such as in the deep-ocean (Grattepanche et al 2018), and their roles in those environments are generally underappreciated (e.g., river and still sparse in soil). In addition to having a better picture of those environments, assessing the diversity of micro- and nano-organisms in various environments will allow us to better apprehend biodiversity and microbial biogeography on Earth and therefore biogeochemical cycles. Another aspect I would like to explore is the time scales of protist community changes related to environmental perturbations (natural or anthropogenic), by starting a survey of a local area (easy sampling) with potential high frequency sampling (up to hourly). This explorative approach will open a lot of collaboration opportunities with other biologists, physicists and chemists for assessing the biotic and abiotic parameters in those peculiar environments.

Another research direction is looking at the relation between microbes and humans. Microbes serve as food resources for many organisms including fish and livestock and cooperate with plants, including crops, for nutrients access. Those microbial eukaryotes can also be detrimental such as parasites (e.g., Entamoeba, Trichodina). In the future, I am planning to look in this direction to help better understand the harmful and positive effect of microbial eukaryotes (e.g., microbiomes of livestock, impact of microbial eukaryotes on aquaculture, etc).

To carried out these research directions, I plan to use (1) microscopy to observe the organisms, (2) molecular tools including single-cell ‘omics and amplicon sequencing using multiple primers targeting the SSU ribosomal gene but also critical proteins such as actine or tubulin. This will help to better delineate species from populations and therefore allow to better estimate biogeography and ecology of the microbial eukaryotes.

Microbial eukaryote functions:

While I continue to explore the spatial and temporal scale of protist diversity, I have begun to use an experimental approach to elucidate the processes that drive these patterns. I created microcosms, small scale replicates of marine environments that can be subject to varying environmental changes, to assess how bottom-up (food resources i.e., phytoplankton) and top-down (predators i.e., copepods) controls change the ciliate community (Grattepanche et al 2020). While we observed that copepods tend to have a preferential feeding toward ciliates without a shell, phytoplankton in bloom condition have a more random effect on their microbial eukaryotic predators. Indeed, none of the replicates showed the same community: while the environment has selected a subset of taxa adapted to the conditions, random effect has selected the dominant taxa (neutrality).

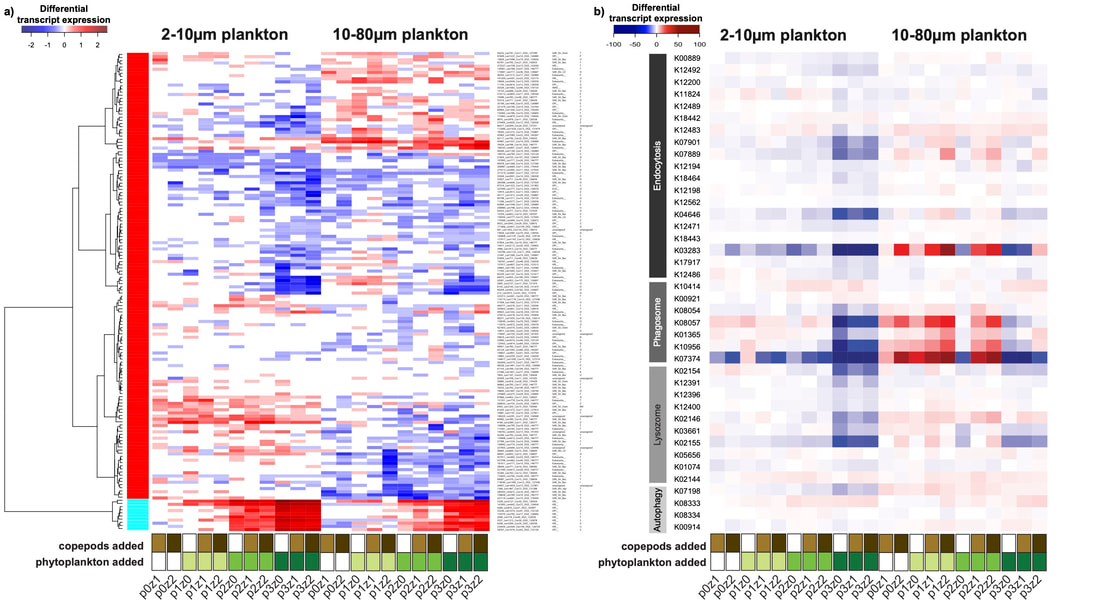

In another pilot study, I combined microcosm and metatranscriptomic approach to assess the genes involved in the food web under bottom-up and top-down control. Metatranscriptomic approaches allow for investigation of the active genetic content of the microbial eukaryotes in various ecosystems. Such analyses will reveal the ecological functions present in the ecosystem and aid in identifying new genes of ecological and biotechnological importance (e.g., toxin production). This work showed (i) a strong effect of phytoplankton bloom on the communities, in particular a strong reduction of the nanoplankton gene diversity and expression, and (ii) top-down control of micro-heterotrophs reduced the grazing impact on phytoplankton bloom (Grattepanche et al 2020).

Heatmap of the transcripts or KO related to phagotrophy. Transcripts and KO were selected based on a) protein identified by Burns et al (2018) and b) KO reported by McKie-Krisberg et al (2018).

Heatmap of the transcripts or KO related to phagotrophy. Transcripts and KO were selected based on a) protein identified by Burns et al (2018) and b) KO reported by McKie-Krisberg et al (2018).

Future Direction:

Contrary to the work done with prokaryotes, the metatranscriptomic approach has revealed some limitation mainly related to the paucity of the database (of the 25% conserved gene family, only 65% were assigned to a function in KEGG). Culture and experiments are a powerful source of information to help solving this issue. Comparative approaches can illuminate some key genes such as genes involved in phagotrophy (culture incubated with or without prey), response to abiotic perturbation (e.g., temperature or pH changes). In addition to better understanding the role of the many genes with unknown function, this will help improve and expand existing databases. When more gene functions are identified, metatranscriptomics will serve as one essential component for assessing ecosystem health: instead of assessing the taxonomic biodiversity, using key genes, we will be able to assess the functional diversity. This may also help to better understand the biogeography and time scales of microbial eukaryotes.

Another method I intend to develop to assess community function is performing transcriptomics on fixed samples. While this approach is yet to be developed for microbial eukaryotes, I am so far able to extract and amplify the transcriptome of protist culture that was fixed and stored for up to a week. This step is not trivial, as it can help better select the cell for transcriptomics by collecting other information, potentially microscopy (fluorescently labelled), and avoid cell stress during the isolation step (cell picking or filtration). This kind of approach will allow tracking the ‘true’ gene expression (reduce amount of stress genes and contaminants when fixated at the sampling site or sampled and fixated simultaneously), which can be related back to ecosystem function. I will resubmitted a promising proposal (10 over 13 reviews from the first two submissions came back as excellent or good) using data collected in antarctica to look at the function of cells and populations using these approaches.

Linking diversity to ecology using evolution:

Ultimately, I intend to better understand the ecological function of plankton communities. My work, like other studies, reveals that the ecology of microbial eukaryotes is poorly understood. I will combine the knowledge from the two previous approaches to create a model linking diversity to microbial eukaryotes functions. In the past decade, metatranscriptomics and metagenomics data have emerged from many environments. The identification of key genes will allow mapping of functions in already available datasets, and create a map of genes, function and taxonomy to be able to predict ecosystem health.

From the many projects that can illuminate the ecology of microbial eukaryotes, one question that attracts me is an old and still open question: the paradox of the plankton (Hutchinson, 1961) or why are there so many planktonic species? Some elements of response include patchiness at small scale (Bracco et al 2000; Rynearson & Menden-Deuer 2016) assuming that many of the structuring factors cannot be measured (Clark et al 2007). My works, as many others, have used molecular tools (ribosomal RNA) to estimate diversity and ecology of protists. While these studies are critical for understanding the biosphere, some issues including the high intra-individual polymorphism of the SSU rDNA make it difficult to directly relate genetics to ecology, with the classic question: what defines a microbial species? What is the time scale of evolution in the protist world? An integrative approach (coupling genetics, morphology, functional traits) will help solving these issues, and better understand the microbial ecology.